Recovering from first metatarsophalangeal joint arthrodesis represents one of the most significant rehabilitation challenges in foot and ankle surgery. The procedure, commonly known as big toe fusion or hallux fusion, permanently alters the biomechanics of the forefoot, requiring patients to adapt their gait patterns and develop new movement strategies. While the surgery effectively eliminates chronic pain associated with severe arthritis or hallux rigidus, the journey back to normal walking involves understanding complex physiological adaptations and following carefully structured rehabilitation protocols.

The process of relearning to walk after big toe fusion extends far beyond simply putting one foot in front of the other. Your body must compensate for the loss of metatarsophalangeal joint mobility, redistributing forces across the foot and developing alternative propulsion mechanisms. This adaptation period typically spans several months and requires patience, dedication, and often professional guidance to achieve optimal functional outcomes.

Understanding hallux rigidus and first metatarsophalangeal joint arthrodesis

Pathophysiology of degenerative joint disease in the hallux

Hallux rigidus develops through a progressive deterioration of the first metatarsophalangeal joint, beginning with minor cartilage damage and evolving into complete joint destruction. The condition affects approximately 2.5% of adults over 50 years old, making it the most common arthritic condition of the foot. Initially, patients experience pain primarily during the push-off phase of gait, when the big toe must dorsiflex to allow normal heel rise and forward propulsion.

The degenerative process involves multiple factors including genetic predisposition, mechanical overloading, and previous trauma. As the condition progresses, osteophyte formation occurs around the joint margins, further restricting motion and increasing pain levels. The cartilage surfaces become irregular and worn, leading to bone-on-bone contact during weight-bearing activities. This pathological process ultimately necessitates surgical intervention when conservative treatments fail to provide adequate symptom relief.

Surgical indications for MTP joint fusion vs cheilectomy

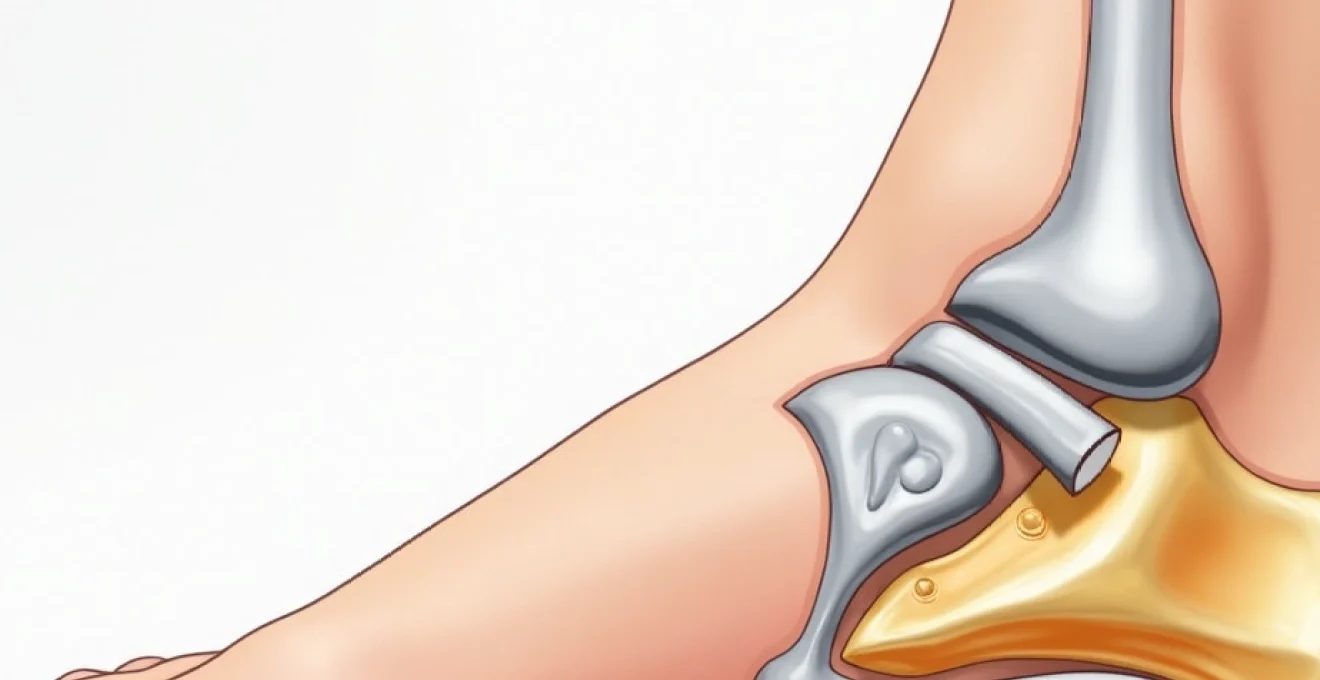

The decision between first metatarsophalangeal joint fusion and cheilectomy depends primarily on the severity of joint destruction and remaining cartilage quality. Cheilectomy, which involves removal of dorsal bone spurs and joint debridement, remains appropriate for early to moderate hallux rigidus where significant cartilage remains intact. However, when joint space narrowing exceeds 50% or when severe deformity is present, arthrodesis becomes the preferred surgical option.

Patient factors also influence surgical selection, including activity level, age, and functional demands. Young, active patients with severe joint destruction benefit from the long-term durability that fusion provides, despite the permanent loss of joint motion. The procedure offers excellent pain relief with satisfaction rates exceeding 90% in most published series. Additionally, fusion eliminates the possibility of recurrent symptoms, making it an attractive option for patients seeking definitive treatment.

Post-operative bone healing timeline and consolidation process

Bone healing following first metatarsophalangeal joint fusion follows predictable biological phases, beginning with inflammatory responses within the first week post-operatively. The initial inflammatory phase triggers cellular recruitment and blood clot formation at the fusion site. During the subsequent reparative phase, spanning weeks 2-6, osteoblasts begin laying down new bone matrix while osteoclasts remove damaged tissue.

The remodelling phase, occurring from 6 weeks to 6 months post-operatively, involves progressive bone strengthening and architectural reorganisation. Radiographic evidence of fusion typically becomes apparent between 8-12 weeks, though complete consolidation may require up to 6 months. Factors affecting healing include patient age, smoking status, nutritional status, and compliance with weight-bearing restrictions. Studies indicate fusion rates of 95-98% when proper surgical technique and post-operative protocols are followed.

Biomechanical alterations following first ray immobilisation

The elimination of first metatarsophalangeal joint motion fundamentally alters forefoot biomechanics, requiring compensatory mechanisms throughout the kinetic chain. Normal gait requires approximately 65-75 degrees of hallux dorsiflexion during terminal stance, a motion that becomes impossible following successful fusion. Consequently, your body must develop alternative strategies to achieve heel rise and forward progression during walking.

The most significant adaptation involves increased reliance on the interphalangeal joint of the hallux, which typically provides 10-15 degrees of compensatory dorsiflexion. Additionally, increased motion occurs at the first tarsometatarsal joint and midfoot structures to accommodate the rigid first ray. These adaptations require time to develop and may initially feel awkward or unnatural. Understanding these biomechanical changes helps set realistic expectations for the recovery process and emphasises the importance of structured rehabilitation.

Gait pattern modifications and compensatory mechanisms

Rocker bottom shoe technology and forefoot rolling motion

Rocker bottom shoes represent the most effective footwear modification for facilitating normal gait patterns after big toe fusion. These specialised shoes feature a curved sole design that promotes smooth heel-to-toe transition without requiring excessive hallux dorsiflexion. The rocker mechanism effectively replaces the lost metatarsophalangeal joint motion, allowing for more natural walking patterns and reduced energy expenditure.

The optimal rocker design positions the apex slightly proximal to the metatarsal heads, typically around 60-65% of total shoe length from the heel. This configuration promotes early heel rise while maintaining stability during midstance. Carbon fibre plates embedded within the sole structure provide additional rigidity and spring-like energy return, further enhancing propulsive efficiency. Many patients find that rocker shoes significantly improve their walking comfort and reduce fatigue during extended activities.

Lateral weight transfer and midfoot compensation strategies

Following big toe fusion, your body naturally develops compensatory weight transfer patterns to accommodate the rigid first ray. Lateral weight shifting becomes more pronounced as forces redistribute towards the lesser metatarsals and lateral foot structures. This adaptation helps maintain balance and propulsion efficiency despite the loss of hallux flexibility.

Midfoot compensation involves increased motion at the transverse tarsal joints and first tarsometatarsal articulation. These joints provide additional flexibility to accommodate ground irregularities and facilitate smooth weight transfer. However, excessive midfoot motion can lead to fatigue and potential overuse injuries if not properly managed through appropriate footwear and activity modification. Gradual conditioning allows these compensatory mechanisms to develop naturally without causing secondary problems.

Ankle dorsiflexion range adaptations during terminal stance

Ankle dorsiflexion requirements increase following big toe fusion as the ankle joint compensates for lost forefoot mobility. Normal terminal stance requires approximately 10-15 degrees of ankle dorsiflexion, but this demand may increase to 15-20 degrees post-fusion to achieve adequate heel rise. Patients with pre-existing ankle stiffness may experience particular difficulty adapting to these increased demands.

Gastrocnemius and soleus flexibility becomes crucial for successful adaptation, as tight posterior muscle groups can impede necessary ankle motion. Regular stretching exercises targeting these muscle groups should begin as soon as post-operative restrictions allow. Additionally, addressing any ankle joint restrictions through manual therapy or mobilisation exercises can significantly improve functional outcomes and reduce compensatory stress on other structures.

Plantar pressure distribution changes across metatarsal heads

Plantar pressure analysis following big toe fusion reveals significant redistributions of loading patterns across the forefoot. Pressure typically increases under the second and third metatarsal heads as these structures assume greater load-bearing responsibilities. This redistribution can lead to metatarsalgia or stress-related injuries if not properly managed through appropriate orthotic interventions.

Studies demonstrate that peak pressures under the second metatarsal head can increase by 15-25% following first metatarsophalangeal joint fusion, highlighting the importance of pressure redistribution strategies.

Orthotic devices play a crucial role in managing these pressure changes by incorporating metatarsal padding, arch support, and pressure-relieving modifications. Custom orthotics designed specifically for post-fusion feet can significantly reduce the risk of secondary problems and improve overall comfort during weight-bearing activities. Regular pressure assessments help monitor adaptation progress and guide orthotic modifications as needed.

Progressive Weight-Bearing protocols and mobilisation strategies

Non-weight bearing phase management with knee scooters

The initial post-operative period typically requires 2-6 weeks of non-weight bearing or protected weight bearing to allow initial bone healing. During this phase, mobility aids such as knee scooters, crutches, or walkers become essential for maintaining independence while protecting the surgical site. Knee scooters offer particular advantages for patients with good balance and upper body strength, providing efficient mobility while keeping weight off the operated foot.

Proper positioning during the non-weight bearing phase involves maintaining the foot in a neutral position and avoiding excessive dependent positioning that can increase swelling. Regular elevation above heart level helps control post-operative oedema and promotes healing. The protective surgical shoe or cast boot should be worn continuously, even during sleep, to prevent accidental weight bearing and maintain proper alignment of the fusion site.

Partial weight bearing progression using CAM walker boots

Transitioning to partial weight bearing typically begins between 2-6 weeks post-operatively, depending on bone quality, fixation stability, and healing progress. CAM walker boots provide excellent protection during this phase while allowing controlled loading of the fusion site. The rigid sole of these boots prevents metatarsophalangeal joint motion while distributing forces evenly across the plantar surface.

Progressive weight bearing should advance gradually, beginning with 25% body weight and increasing by 25% weekly as tolerated. Digital scales can help monitor loading progression , ensuring compliance with prescribed weight limits. Pain levels should remain minimal during weight bearing advancement; significant discomfort may indicate premature progression or healing complications requiring medical evaluation.

Transition to Rigid-Soled footwear and carbon fibre plates

The transition from protective boots to regular footwear represents a crucial milestone in the recovery process, typically occurring 6-8 weeks post-operatively following radiographic confirmation of bone healing. Rigid-soled shoes with carbon fibre plates provide the ideal intermediate step between protective boots and regular footwear. These modifications limit metatarsophalangeal joint motion while allowing gradual adaptation to normal shoe gear.

Carbon fibre plates should extend from the heel to the toe box, providing complete rigidity across the forefoot. The plate thickness typically ranges from 1-3mm, with thicker plates providing greater rigidity for patients requiring maximum motion control. As adaptation progresses and symptoms resolve, plate thickness can be gradually reduced or eliminated entirely, depending on individual tolerance and activity demands.

Range of motion exercises for adjacent joint structures

Maintaining mobility in adjacent joint structures becomes crucial for preventing compensatory stiffness and dysfunction during the fusion healing process. Ankle range of motion exercises should begin within the first week post-operatively, focusing on plantarflexion, dorsiflexion, and circumduction movements. These exercises help prevent adhesion formation and maintain circulation to promote healing.

Lesser toe range of motion exercises also play an important role in maintaining forefoot flexibility and preventing secondary stiffness. Gentle flexion, extension, and spreading exercises can be performed multiple times daily once initial post-operative pain subsides. Manual stretching of the interphalangeal joint of the big toe becomes particularly important as this joint must provide compensatory motion for the fused metatarsophalangeal joint.

Scar tissue management and soft tissue mobilisation techniques

Scar tissue formation around the fusion site and surgical incision can significantly impact functional outcomes if not properly managed. Gentle massage techniques should begin approximately 2-3 weeks post-operatively once the incision has healed sufficiently. Cross-friction massage helps prevent excessive scar tissue formation while promoting healthy tissue remodelling.

Professional soft tissue mobilisation techniques, including myofascial release and trigger point therapy, can address compensatory muscle tension that develops throughout the recovery process. The plantar fascia, calf muscles, and intrinsic foot muscles often require attention as they adapt to altered biomechanics. Regular soft tissue maintenance helps prevent secondary problems and promotes optimal functional adaptation.

Adaptive footwear solutions and orthotic interventions

Footwear selection becomes critically important following big toe fusion, as inappropriate shoes can significantly impede functional recovery and increase the risk of secondary complications. The ideal post-fusion shoe incorporates several key features including adequate toe box depth, rigid sole construction, and proper heel height limitations. Shoes with excessive heel elevation greater than one inch should be avoided as they place increased demands on the fused joint and may cause discomfort.

Custom orthotic devices provide essential support for managing the biomechanical changes that occur following fusion surgery. These devices typically incorporate metatarsal padding to redistribute pressure away from the second and third metatarsal heads, arch support to control midfoot compensation, and heel posting to optimise rearfoot alignment. The orthotic design must accommodate the rigid first ray while providing appropriate support for the remaining mobile foot structures.

Research indicates that patients using custom orthotics following big toe fusion report 40% greater satisfaction with their walking ability compared to those using over-the-counter insoles alone.

Rocker sole modifications represent the gold standard for post-fusion footwear, with various configurations available depending on individual needs and activity levels. Mild rockers work well for sedentary individuals, while more aggressive rocker designs benefit active patients requiring enhanced propulsive assistance. Some patients require multiple shoe modifications to accommodate different activity levels, including work shoes, athletic footwear, and casual walking shoes.

Physical therapy rehabilitation protocols for hallux fusion recovery

Structured physical therapy plays a vital role in optimising functional outcomes following big toe fusion surgery. The rehabilitation process typically begins 2-3 weeks post-operatively with gentle range of motion exercises for adjacent joints and basic gait training within weight-bearing restrictions. Early intervention helps prevent complications such as joint stiffness, muscle weakness, and compensatory movement patterns that can impede long-term recovery.

The progressive rehabilitation protocol advances through distinct phases, beginning with protection and early mobility, progressing to strengthening and endurance training, and culminating in functional integration and activity-specific training. Each phase builds upon the previous achievements while respecting tissue healing constraints and individual patient capabilities. Balance training becomes particularly important as patients must adapt to altered proprioceptive feedback from the fused joint.

Strengthening exercises focus on maintaining and improving function in the remaining mobile joints of the foot and ankle complex. Calf strengthening helps compensate for altered push-off mechanics, while intrinsic foot muscle training supports arch stability and lesser toe function. Hip and core strengthening also contribute to overall gait stability and may help prevent compensatory problems in the kinetic chain.

Gait training represents a crucial component of the rehabilitation process, helping patients develop efficient walking patterns despite the biomechanical constraints imposed by joint fusion. Therapists use various techniques including treadmill training, overground walking practice, and functional movement patterns to facilitate optimal gait adaptation. Video analysis can provide valuable feedback for identifying and correcting compensatory movement patterns that may lead to secondary problems.

Long-term functional outcomes and activity modification strategies

Long-term studies demonstrate excellent functional outcomes following first metatarsophalangeal joint fusion, with satisfaction rates consistently exceeding 90% at five-year follow-up intervals. Most patients report significant pain reduction and improved quality of life despite the permanent loss of joint motion. The ability to return to recreational activities remains high, with approximately 85% of patients resuming their pre-operative activity levels within 6-12 months of surgery.

Sports participation following big toe fusion requires individual assessment based on activity demands and personal risk tolerance. Low-impact activities such as swimming, cycling, and walking typically pose no restrictions and can be resumed as soon as comfort allows. Running remains possible for most patients, though some modification in technique or footwear may be necessary to accommodate the altered forefoot mechanics.

High-impact and cutting sports present greater challenges due to the increased demands placed on the fused joint and surrounding structures. Sports such as tennis, basketball, and soccer may require more extensive activity modification or alternative exercise choices. However, recreational participation in these activities remains possible with appropriate footwear modifications, gradual conditioning, and realistic expectation setting.

Workplace accommodations may be necessary for patients whose occupations involve prolonged standing, walking on uneven surfaces, or wearing restrictive footwear. Simple modifications such as anti-fatigue mats, flexible break schedules, and appropriate shoe gear can significantly improve occupational comfort and productivity. Most patients successfully return to their pre-operative work activities with minimal or no accommodations required.

The psychological adaptation to permanent joint stiffness represents an often-overlooked aspect of recovery, requiring patience and realistic goal-setting to achieve optimal outcomes. Many patients experience an initial period of frustration as they adjust to altered movement patterns and footwear limitations. Open communication with healthcare providers about expectations and concerns facilitates successful adaptation and helps identify potential issues before they become problematic.

Preventive strategies for long-term foot health include regular foot examinations, appropriate footwear maintenance, and early intervention for any developing problems. Weight management, smoking cessation, and maintaining good cardiovascular health all contribute to optimal healing and long-term success. Patients who embrace these lifestyle modifications typically experience the best functional outcomes and highest satisfaction levels with their surgical results.

The journey of learning to walk again after big toe fusion ultimately represents a testament to the human body’s remarkable ability to adapt and compensate. While the recovery process requires dedication, patience, and often professional guidance, the vast majority of patients successfully return to their desired activity levels with significant pain reduction. Understanding the biomechanical changes, following appropriate rehabilitation protocols, and making necessary lifestyle adaptations form the foundation for achieving optimal long-term outcomes and returning to an active, pain-free lifestyle.

Most importantly, maintaining realistic expectations while remaining committed to the rehabilitation process enables patients to achieve their maximum functional potential following this life-changing procedure. The investment in proper recovery techniques and adaptive strategies pays dividends in improved quality of life and sustained functional independence for years to come. With proper preparation, guidance, and commitment, learning to walk again after big toe fusion becomes not just possible, but highly successful for the overwhelming majority of patients who undergo this transformative surgical intervention.