Unilateral temple headaches represent one of the most concerning neurological presentations in clinical practice, often signalling underlying vascular, neurological, or inflammatory pathology. These localised cephalic pains can range from benign tension-type episodes to life-threatening conditions requiring immediate intervention. The temporal region’s rich vascular and neural supply makes it particularly susceptible to various pathophysiological processes, creating a complex diagnostic challenge for healthcare practitioners.

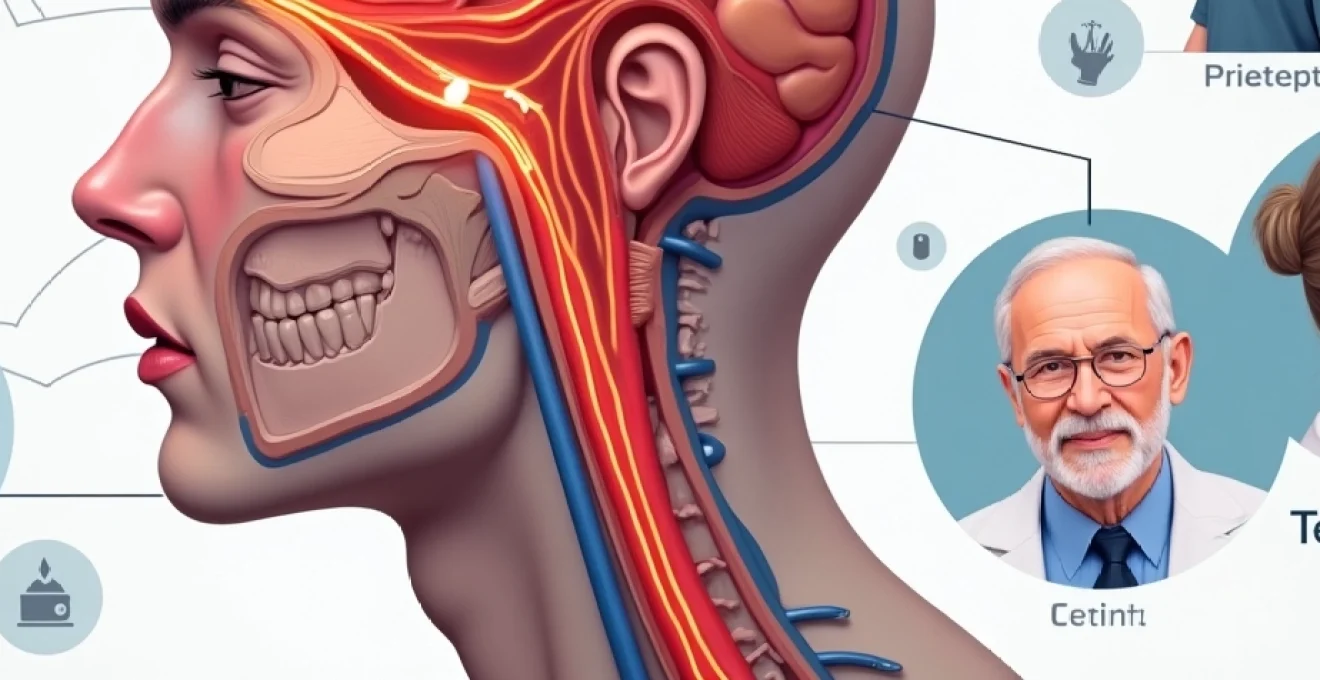

Understanding the intricate anatomy of the temporal region is crucial for proper diagnosis. The superficial temporal artery, branches of the trigeminal nerve, and connections to deeper vascular structures all contribute to the complex pain patterns experienced in this area. When patients present with persistent, severe, or unusual temple pain, rapid assessment and appropriate treatment protocols can prevent serious complications including permanent vision loss or stroke.

Primary vascular causes of unilateral temple headache

Vascular pathology represents the most serious category of temple-specific headache disorders, encompassing conditions that directly affect blood vessels supplying the cranial structures. These disorders often present with distinctive clinical patterns that aid in differential diagnosis and treatment selection.

Temporal arteritis and giant cell arteritis pathophysiology

Giant cell arteritis (GCA), also known as temporal arteritis, stands as the most critical vascular cause of temple headache in patients over 50 years of age. This systemic vasculitis primarily affects large and medium-sized arteries, with a particular predilection for the superficial temporal, ophthalmic, and posterior ciliary arteries. The inflammatory process involves T-cell mediated immune responses, leading to arterial wall thickening, luminal narrowing, and potential complete occlusion.

The clinical presentation typically includes severe, constant temple pain accompanied by jaw claudication, scalp tenderness, and constitutional symptoms such as fever, weight loss, and malaise. Visual symptoms occur in approximately 15-20% of cases , ranging from transient visual obscurations to permanent monocular blindness. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels are markedly elevated in most cases, though normal inflammatory markers do not exclude the diagnosis.

Temporal artery biopsy remains the gold standard for diagnosis, revealing characteristic inflammatory infiltrates with multinucleated giant cells, though skip lesions can result in false-negative results. Treatment requires immediate high-dose corticosteroid therapy, typically prednisolone 1mg/kg daily, to prevent irreversible visual complications. Response to treatment is usually dramatic, with headache resolution occurring within 24-48 hours of steroid initiation.

Migraine-associated vasodilation in superficial temporal artery

Migraine headaches frequently manifest with unilateral temple pain due to the complex neurovascular mechanisms involving the trigeminovascular system. During migraine attacks, vasodilation of the superficial temporal artery contributes to the characteristic throbbing, pulsatile quality of pain. This vascular component is mediated by calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) release from trigeminal nerve endings, causing neurogenic inflammation and arterial dilation.

The temporal location of migraine pain often correlates with the distribution of the first division of the trigeminal nerve (V1), which innervates the forehead and anterior temple region. Patients typically describe a gradual onset of throbbing pain that may be preceded by visual aura symptoms, including scintillating scotomas or fortification spectra. Associated symptoms include photophobia, phonophobia, nausea, and vomiting, which help distinguish migraine from other temple headache causes.

Contemporary migraine treatment involves both acute and preventive strategies. Triptans, CGRP receptor antagonists, and anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies have revolutionised migraine management by specifically targeting the neurovascular mechanisms underlying temple pain. The temporal artery’s superficial location also makes it accessible for non-invasive neuromodulation techniques, including external trigeminal nerve stimulation.

Cluster headache Trigemino-Vascular pathway activation

Cluster headaches produce some of the most severe temple and orbital pain known to medicine, earning them the designation “suicide headaches” due to their excruciating intensity. The pathophysiology involves activation of the posterior hypothalamus, leading to trigeminovascular system stimulation and subsequent release of vasoactive neuropeptides. This process results in intense unilateral orbital, supraorbital, and temporal pain lasting 15 minutes to 3 hours.

The temporal pain in cluster headaches is characteristically accompanied by ipsilateral autonomic symptoms, including conjunctival injection, lacrimation, nasal congestion, rhinorrhoea, and partial Horner’s syndrome. The circadian pattern of attacks, often occurring at the same time each day and awakening patients from sleep, suggests hypothalamic involvement. The pain quality is typically described as boring, burning, or stabbing, centred around the temple and orbital regions.

Acute treatment requires rapid-acting interventions due to the brief duration of attacks. High-flow oxygen therapy at 12-15 litres per minute provides relief in 70-80% of patients within 15 minutes. Subcutaneous sumatriptan 6mg represents the most effective pharmacological acute treatment, with response rates exceeding 90%. Preventive treatment during cluster periods often requires verapamil, with some patients requiring high doses under cardiac monitoring.

Carotid artery dissection and ipsilateral temple pain

Carotid artery dissection presents a critical vascular emergency that can manifest with temple headache as the primary symptom. This condition involves a tear in the arterial wall, creating an intramural haematoma that may compress the true lumen or extend into the subarachnoid space. Temple pain associated with carotid dissection typically has a sudden onset and may be accompanied by neck pain, Horner’s syndrome, or neurological deficits.

The mechanism of temple pain in carotid dissection relates to the rich innervation of the carotid sheath by sympathetic fibres and branches of the glossopharyngeal and vagus nerves. Stretching of these neural structures by the expanding haematoma produces characteristic pain patterns radiating to the temple, orbit, and neck regions. The presence of concurrent neurological symptoms, particularly transient ischaemic attacks or stroke, should raise immediate suspicion for this diagnosis.

Diagnostic imaging with CT angiography or MR angiography reveals the characteristic appearances of arterial dissection, including luminal narrowing, wall thickening, or pseudoaneurysm formation. Treatment typically involves anticoagulation to prevent thromboembolic complications, though antiplatelet therapy may be preferred in certain circumstances. The temple headache often resolves as the arterial healing progresses over weeks to months.

Neurological triggers behind Temple-Specific pain patterns

Neurological causes of temple headache involve dysfunction or irritation of specific neural pathways that innervate the temporal region. These conditions often present with characteristic pain patterns and associated neurological symptoms that aid in diagnostic differentiation. Understanding the complex innervation of the temporal area is essential for accurate diagnosis and targeted treatment approaches.

Trigeminal nerve branch dysfunction and V1 distribution

The first division of the trigeminal nerve (ophthalmic division or V1) provides sensory innervation to the temple, forehead, and upper eyelid regions. Dysfunction of this nerve branch can result from various pathological processes, including inflammation, compression, or demyelination. Trigeminal neuralgia affecting the V1 distribution is less common than involvement of the maxillary (V2) or mandibular (V3) divisions but produces characteristic sharp, electric shock-like pains in the temple and forehead areas.

The pain pattern in V1 trigeminal neuralgia typically follows the anatomical distribution of the supraorbital and supratrochlear nerves, creating a distinct territorial pattern of pain localisation. Patients describe brief, lancinating pains that may be triggered by light touch, wind exposure, or specific movements. Unlike other forms of headache, trigeminal neuralgia has a refractory period following each attack during which further stimulation does not trigger pain.

Treatment of V1 trigeminal neuralgia often requires anticonvulsant medications, with carbamazepine remaining the first-line therapy despite its side effect profile. Gabapentin, pregabalin, and baclofen represent alternative options for patients intolerant of carbamazepine. In refractory cases, surgical interventions including gamma knife radiosurgery or microvascular decompression may be considered to achieve long-term pain relief.

Occipital neuralgia referred pain to temporal region

Occipital neuralgia involves irritation or inflammation of the greater, lesser, or third occipital nerves, which can produce referred pain patterns extending to the temporal region through complex neural connections. The greater occipital nerve, arising from the C2 spinal nerve, has anatomical connections with the trigeminal system that can result in referred pain patterns affecting the temple and frontal regions .

The characteristic pain of occipital neuralgia begins at the suboccipital region and radiates over the posterior scalp, but convergence mechanisms in the trigeminocervical complex can produce simultaneous temple pain. This creates a distinctive pain pattern that patients often describe as shooting or electric-like, originating from the neck and extending around to the temple. Tenderness over the greater occipital nerve emergence point, located medial to the mastoid process, supports this diagnosis.

Diagnostic nerve blocks using local anaesthetic at the greater occipital nerve emergence point provide both diagnostic confirmation and temporary therapeutic relief. Treatment options include nerve blocks with corticosteroids, radiofrequency ablation, or surgical neurolysis for refractory cases. Physical therapy addressing cervical spine dysfunction often provides additional benefit, as cervical pathology frequently contributes to occipital nerve irritation.

Temporomandibular joint disorder myofascial referral

Temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorders represent a common but frequently overlooked cause of temple headache. The complex anatomy of the TMJ includes multiple muscles of mastication, joint structures, and neural innervation that can produce referred pain patterns extending to the temporal region. Myofascial pain originating from the temporalis muscle directly produces temple tenderness and headache symptoms that may be mistaken for primary headache disorders.

The temporalis muscle, one of the primary muscles of mastication, covers much of the temporal region and can develop trigger points that produce localised and referred pain. Dysfunction of the masseter, medial pterygoid, and lateral pterygoid muscles can also contribute to temple pain through complex referral patterns. Patients often report associated symptoms including jaw clicking, limited mouth opening, and pain with chewing or speaking.

Clinical examination reveals tenderness over the temporalis muscle, restricted jaw movement, and potential joint sounds during mandibular motion. Treatment approaches include occlusal splint therapy, physical therapy focusing on jaw mobility and muscle relaxation, and trigger point injections. Addressing underlying dental malocclusion or parafunctional habits such as bruxism is essential for long-term symptom resolution.

Cervicogenic headache C2-C3 nerve root involvement

Cervicogenic headaches arise from disorders of the upper cervical spine, particularly involving the C1-C3 vertebral segments and their associated neural structures. The trigeminocervical nucleus, where trigeminal and upper cervical afferents converge, provides the anatomical basis for referred pain from cervical structures to the temple region. C2-C3 nerve root dysfunction can produce temple pain through this convergence mechanism, creating headache patterns that may be indistinguishable from primary headache disorders.

The clinical presentation of cervicogenic headache often includes unilateral temple and frontal pain accompanied by neck pain and stiffness. Pain typically originates from the occiput and spreads anteriorly to the temple and forehead regions. Patients may report that head and neck movements precipitate or worsen their headache symptoms, providing an important diagnostic clue. Reduced cervical range of motion and tenderness over the upper cervical segments support this diagnosis.

Diagnostic confirmation often requires controlled diagnostic blocks of the C2-C3 medial branch nerves or third occipital nerve. Treatment approaches include manual therapy techniques, therapeutic exercises targeting cervical mobility and strength, and interventional procedures such as radiofrequency neurotomy for facet joint-mediated pain. Addressing underlying cervical spine pathology, including disc degeneration or facet arthropathy, is crucial for sustained symptom improvement.

Secondary pathological conditions causing unilateral temple headache

Secondary headache disorders encompass a broad spectrum of underlying pathological conditions that manifest with temple pain as a prominent feature. These conditions often require specific diagnostic approaches and targeted treatments based on the underlying aetiology. Recognition of red flag symptoms is crucial for timely diagnosis and prevention of serious complications.

Intracranial pathology represents one of the most serious categories of secondary temple headache. Brain tumours, particularly those located in the frontal or temporal lobes, can produce localised headache patterns due to mass effect or involvement of pain-sensitive structures. Meningiomas arising from the sphenoid wing or temporal fossa commonly present with unilateral temple pain that may be progressive in nature. The headache pattern often differs from the patient’s usual headache type and may be associated with focal neurological signs or seizures.

Increased intracranial pressure from various causes, including idiopathic intracranial hypertension, hydrocephalus, or cerebral oedema, can manifest with temple headache that worsens with Valsalva manoeuvres or positional changes. The headache is typically worse in the morning and may be accompanied by visual symptoms, including transient visual obscurations or diplopia. Papilloedema on fundoscopic examination provides crucial diagnostic information in these cases.

Infectious processes affecting the central nervous system can also present with temple headache as a prominent feature. Meningitis, encephalitis, or brain abscesses may produce severe headache with associated fever, neck stiffness, and altered mental status. Sinusitis, particularly involving the sphenoid or frontal sinuses, can refer pain to the temple region and may be accompanied by purulent nasal discharge or facial tenderness. Careful assessment for systemic signs of infection is essential in these presentations.

Medication overuse headache represents an increasingly common secondary cause of temple pain, particularly in patients with underlying primary headache disorders who frequently use acute headache medications. The overuse of simple analgesics, combination medications, or triptans can lead to a chronic daily headache pattern that includes temple pain. The headache pattern often changes from the original primary headache type and may become more diffuse or constant in nature.

Systemic conditions can also manifest with temple headache as part of their clinical presentation. Hypertensive headaches, although less common than previously thought, can present with temple pain during hypertensive crises. Giant cell arteritis, as discussed previously, represents a systemic inflammatory condition with particular predilection for temporal artery involvement. Other vasculitic conditions, including polyarteritis nodosa or systemic lupus erythematosus, may rarely present with temple headache due to cerebral vasculitis.

Diagnostic differentiation through clinical presentation patterns

Accurate diagnosis of unilateral temple headache requires systematic evaluation of pain characteristics, associated symptoms, temporal patterns, and response to treatment. The development of standardised diagnostic criteria for primary headache disorders has improved diagnostic accuracy, but secondary causes must always be carefully excluded, particularly in patients presenting with new-onset or changing headache patterns.

The temporal pattern of headache onset provides crucial diagnostic information. Sudden-onset headache reaching maximum intensity within minutes suggests subarachnoid haemorrhage, carotid dissection, or other vascular emergencies. Gradual onset over hours to days may suggest migraine, tension-type headache, or inflammatory conditions. Progressive headache worsening over weeks to months raises concern for secondary pathology, including intracranial masses or chronic inflammatory conditions.

Pain quality assessment helps differentiate between various headache types. The throbbing, pulsatile quality typical of migraine contrasts with the constant, burning pain of giant cell arteritis or the sharp, electric-like quality of trigeminal neuralgia. The excruciating, boring quality of cluster headache is distinctive and rarely confused with other headache types once experienced. Duration of individual episodes also provides diagnostic clues, with cluster headaches lasting 15 minutes to 3 hours, migraines lasting 4-72 hours, and tension-

type headaches having variable durations often lasting days to weeks.Associated symptoms provide valuable diagnostic differentiation. The autonomic features of cluster headache, including conjunctival injection, lacrimation, and nasal congestion, are pathognomonic when present. Migraine-associated symptoms such as photophobia, phonophobia, nausea, and vomiting help distinguish it from tension-type headache or secondary causes. Constitutional symptoms including fever, weight loss, and malaise strongly suggest inflammatory conditions such as giant cell arteritis or infectious processes.Physical examination findings contribute significantly to diagnostic accuracy. Temporal artery prominence, tenderness, or absence of pulsation suggests giant cell arteritis and warrants immediate investigation. Fundoscopic examination may reveal papilloedema in cases of increased intracranial pressure or arteriovenous nicking in hypertensive patients. Cervical spine examination, including range of motion assessment and palpation for trigger points, helps identify cervicogenic headache causes.Neurological examination must assess for focal deficits that might suggest secondary pathology. Horner’s syndrome ipsilateral to the headache may indicate carotid dissection or cluster headache. Trigeminal nerve function testing, including corneal reflex assessment and facial sensation mapping, can identify trigeminal neuralgia or other cranial nerve pathology. Any focal neurological signs warrant immediate neuroimaging to exclude structural causes.Laboratory investigations play a crucial role in specific clinical scenarios. Elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein levels support the diagnosis of giant cell arteritis, though normal values do not exclude this condition. Complete blood count may reveal anaemia of chronic disease in inflammatory conditions or elevated white cell count in infectious processes. Lumbar puncture becomes necessary when meningitis or subarachnoid haemorrhage is suspected.Neuroimaging selection depends on clinical presentation and suspected pathology. Magnetic resonance imaging with angiography provides optimal assessment for vascular pathology, including carotid dissection or cerebral vasculitis. Computed tomography angiography offers rapid vascular assessment in emergency situations. High-resolution MRI sequences can identify inflammatory changes in the temporal artery wall, providing a non-invasive alternative to temporal artery biopsy in selected cases.

Evidence-based treatment protocols for temple-localised cephalgia

Effective management of temple-localised headache requires accurate diagnosis followed by implementation of evidence-based treatment protocols tailored to the specific underlying pathophysiology. Treatment approaches must consider both acute symptom relief and long-term preventive strategies while addressing potential complications and monitoring for treatment-related adverse effects.Acute treatment protocols vary significantly based on the underlying headache type and severity of presentation. For suspected giant cell arteritis, immediate high-dose corticosteroid therapy represents a medical emergency to prevent irreversible visual complications. Prednisolone 1mg/kg daily, typically 60-80mg, should be initiated promptly, even before confirmatory testing is completed. The dramatic response to steroids within 24-48 hours provides both therapeutic benefit and diagnostic confirmation. Alternative corticosteroids such as methylprednisolone may be used intravenously in severe cases or when oral administration is not possible.Migraine-specific acute treatments targeting the trigeminovascular system provide optimal relief for temple-localised migraine pain. Triptans remain the gold standard for moderate to severe migraine attacks, with subcutaneous sumatriptan providing the most rapid onset of action. Oral triptans including rizatriptan, eletriptan, and almotriptan offer convenient administration with high efficacy rates. The newer gepants, including ubrogepant and rimegepant, provide effective acute treatment with fewer contraindications than triptans, particularly beneficial for patients with cardiovascular comorbidities.Cluster headache acute treatment requires rapid-acting interventions due to the brief attack duration and extreme pain intensity. High-flow oxygen therapy at 12-15 litres per minute through a non-rebreather mask provides relief in 70-80% of patients within 15 minutes and represents the safest acute treatment option. Subcutaneous sumatriptan 6mg achieves response rates exceeding 90% within 15 minutes, making it the most effective pharmacological acute treatment. Nasal zolmitriptan 5mg offers a non-injectable alternative with good efficacy, particularly useful for patients uncomfortable with self-injection.Preventive treatment strategies become essential for patients experiencing frequent or severe temple headaches. Migraine prevention requires consideration of comorbid conditions, medication tolerability, and patient preferences. Topiramate, propranolol, and amitriptyline represent first-line preventive options with substantial evidence support. The newer anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies, including erenumab, fremanezumab, and galcanezumab, provide highly effective prevention with excellent tolerability profiles, particularly beneficial for patients with frequent temple-localised migraines.Cluster headache prevention during active cluster periods requires different strategies due to the condition’s episodic nature and circadian patterns. Verapamil remains the gold standard preventive treatment, though high doses up to 480mg daily may be required, necessitating cardiac monitoring with electrocardiograms. Lithium carbonate provides alternative prevention, particularly for chronic cluster headache, though requires regular monitoring of serum levels and renal function. Transitional treatments including corticosteroids or ergotamine provide rapid onset prevention while waiting for verapamil to achieve therapeutic effect.Interventional treatments offer valuable options for refractory temple headache cases. Greater occipital nerve blocks using local anaesthetic and corticosteroids provide both diagnostic and therapeutic benefits for occipital neuralgia with temple referral patterns. Trigger point injections targeting temporalis muscle trigger points can effectively address TMJ-related temple pain. Botulinum toxin injections, while primarily indicated for chronic migraine prevention, show particular efficacy for temple-localised pain patterns due to the superficial location of injection sites.Neuromodulation techniques represent emerging treatment options for refractory temple headache conditions. External trigeminal nerve stimulation devices provide non-invasive acute and preventive treatment options for migraine and cluster headache. Occipital nerve stimulation shows promise for chronic daily headache with occipital and temple pain components. Sphenopalatine ganglion stimulation devices offer innovative treatment approaches for cluster headache prevention with encouraging clinical trial results.Surgical interventions become necessary in specific circumstances, particularly for structural causes of secondary headache. Temporal artery biopsy remains essential for giant cell arteritis diagnosis, though the procedure must be performed carefully to avoid false-negative results from skip lesions. Microvascular decompression provides definitive treatment for trigeminal neuralgia affecting the V1 distribution, though the procedure carries inherent surgical risks that must be weighed against potential benefits.Treatment monitoring requires regular follow-up assessments to evaluate therapeutic response, identify adverse effects, and adjust treatment protocols as needed. Giant cell arteritis treatment requires careful corticosteroid tapering over 12-24 months, with regular monitoring of inflammatory markers and clinical symptoms. Migraine preventive treatments need 2-3 months for full efficacy assessment, with dose adjustments based on headache frequency reduction and tolerability. Patient-reported outcome measures including headache diaries and quality of life assessments provide objective treatment monitoring tools.Lifestyle modifications and non-pharmacological approaches complement medical treatments for temple headache management. Stress reduction techniques, regular sleep schedules, and identification of individual headache triggers provide important adjunctive benefits. Physical therapy addressing cervical spine dysfunction and muscle tension can effectively treat cervicogenic and tension-type headache components. Dietary modifications, including elimination of known migraine triggers and maintaining regular meal schedules, support overall headache management strategies.Patient education plays a crucial role in successful long-term temple headache management. Understanding headache triggers, proper acute medication use, and recognition of warning symptoms requiring immediate medical attention empowers patients to participate actively in their care. Headache diary maintenance helps identify patterns and triggers while providing objective measures of treatment efficacy. Clear instructions regarding when to seek emergency care ensure appropriate utilisation of healthcare resources and prevention of serious complications.Long-term prognosis for temple headache varies significantly based on underlying aetiology and treatment response. Primary headache disorders, including migraine and cluster headache, represent chronic conditions requiring ongoing management, though many patients achieve excellent symptom control with appropriate treatment. Secondary headache causes often resolve with successful treatment of the underlying condition, though some may require long-term monitoring for recurrence. Early diagnosis and appropriate treatment initiation provide the best outcomes for preventing complications and maintaining quality of life.