The human head contains an intricate network of interconnected nerves, blood vessels, and anatomical structures that can create surprising patterns of referred pain. When dental issues trigger discomfort that radiates to the eye region, patients often find themselves puzzled by this seemingly unrelated connection. This phenomenon occurs far more frequently than many people realise, affecting thousands of individuals who experience simultaneous tooth and eye pain without understanding the underlying mechanisms.

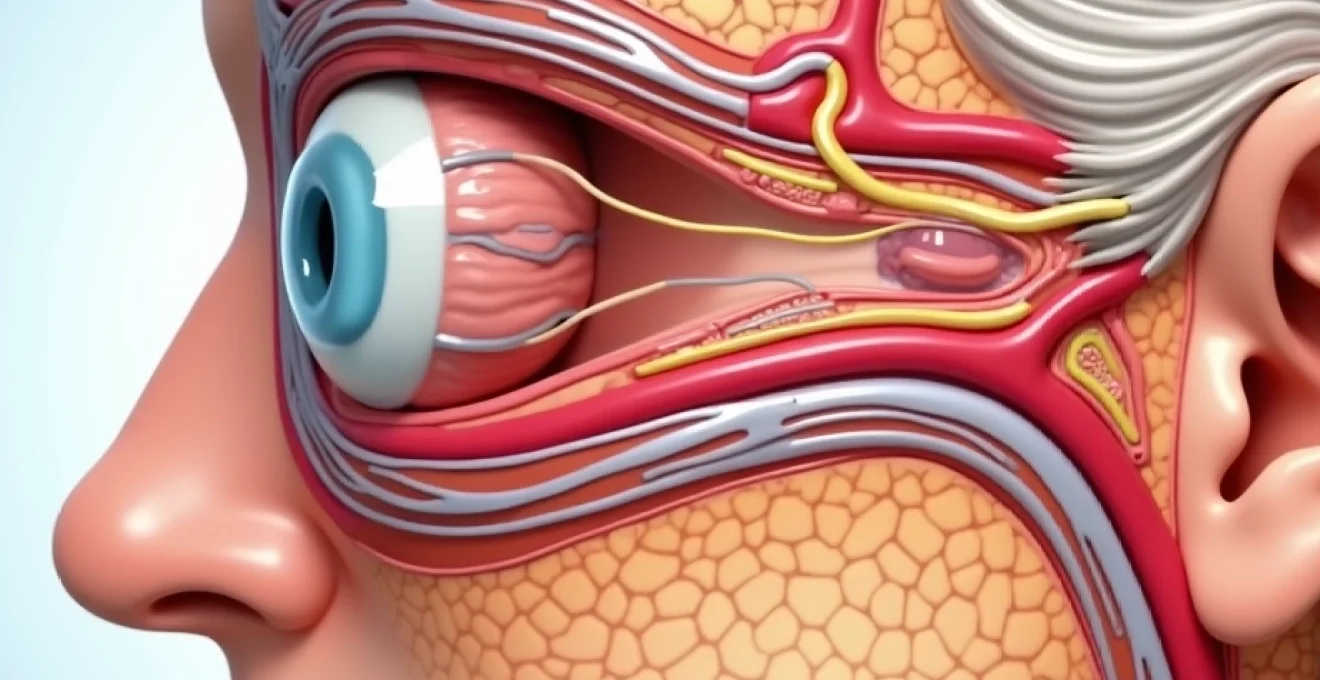

The relationship between dental pain and ocular discomfort stems from shared neural pathways, particularly involving the trigeminal nerve system. This complex anatomical arrangement means that inflammation, infection, or trauma affecting one area can manifest as pain in seemingly distant locations. Understanding these connections proves essential for both patients and healthcare providers in achieving accurate diagnosis and effective treatment outcomes.

Anatomical connections between trigeminal and ophthalmic neural pathways

The trigeminal nerve, also known as cranial nerve V, serves as the primary sensory nerve for the face and head region. This massive neural structure divides into three distinct branches: the ophthalmic division (V1), maxillary division (V2), and mandibular division (V3). Each branch carries sensory information from specific regions, but their close anatomical proximity and shared central processing centres create opportunities for cross-referral of pain signals.

Trigeminal nerve branch distribution and maxillary division overlap

The maxillary division of the trigeminal nerve innervates the upper teeth, maxillary sinus, and portions of the midface region. This branch contains numerous smaller nerve fibres that extend throughout the maxillary bone structure, creating an extensive sensory network. When upper molars become infected or inflamed, the resulting neural stimulation can activate adjacent nerve pathways that serve the orbital and periorbital regions.

Research demonstrates that approximately 15-20% of patients with maxillary dental infections report concurrent eye pain or pressure sensations. The anatomical convergence occurs primarily at the sphenopalatine ganglion, where multiple nerve branches intersect and share processing pathways. This convergence explains why upper tooth pain frequently manifests as deep, aching sensations behind or around the affected eye.

Ophthalmic division of cranial nerve V and orbital pain referral

The ophthalmic division carries sensory information from the forehead, upper eyelid, and portions of the nasal cavity. Its proximity to maxillary nerve branches creates multiple opportunities for cross-innervation and shared pain processing. When dental inflammation occurs in the posterior maxillary region, inflammatory mediators can affect nearby ophthalmic nerve fibres, resulting in referred pain patterns.

Clinical studies indicate that patients with upper premolar or molar infections experience ophthalmic-type pain in roughly 25% of cases. The pain typically presents as a dull, persistent ache that worsens with head movement or changes in position. This occurs because the ophthalmic nerve shares central processing regions with maxillary nerve fibres in the trigeminal sensory nucleus.

Greater superficial petrosal nerve Cross-Innervation mechanisms

The greater superficial petrosal nerve represents another critical pathway connecting dental and ocular pain perception. This parasympathetic nerve branch carries fibres that influence tear production and orbital blood flow. During periods of intense dental inflammation, particularly from maxillary abscesses, inflammatory mediators can affect petrosal nerve function, leading to altered tear production and orbital discomfort.

Patients experiencing this type of cross-innervation often report excessive tearing, burning sensations around the eye, and sensitivity to light alongside their dental pain. The mechanism involves inflammatory cytokines that affect nerve membrane permeability, creating abnormal signal transmission patterns throughout the interconnected neural network.

Sphenopalatine ganglion neural network convergence

The sphenopalatine ganglion functions as a critical relay station for multiple nerve pathways affecting both dental and ocular regions. This small but important structure receives input from maxillary nerve branches, parasympathetic fibres from the facial nerve, and sympathetic fibres from the carotid plexus. When dental infections create inflammatory changes in this region, the resulting neural dysfunction can produce complex pain patterns involving both teeth and eyes.

The sphenopalatine ganglion’s strategic location makes it a crucial intersection point for understanding referred pain patterns between dental and ocular regions. Dysfunction in this area often produces characteristic symptoms including nasal congestion, eye pain, and dental sensitivity occurring simultaneously. Treatment targeting this ganglion through specific nerve blocks can provide significant relief for patients experiencing complex pain patterns.

Maxillary sinusitis and referred ocular pain syndromes

The maxillary sinuses maintain intimate anatomical relationships with both the upper teeth and orbital structures. These air-filled cavities extend from the nasal cavity to areas immediately adjacent to the maxillary tooth roots and orbital floor. When sinus inflammation occurs, whether from dental infection or primary sinusitis, the resulting pressure and inflammatory changes can create pain patterns affecting multiple regions simultaneously.

Acute maxillary sinusitis with secondary orbital pressure

Acute maxillary sinusitis frequently originates from dental infections, particularly involving the upper premolars and molars. The tooth roots of these teeth extend into or very close to the maxillary sinus floor, creating direct pathways for bacterial spread. When infection ascends from the tooth root into the sinus cavity, the resulting inflammation produces significant pressure changes that affect adjacent orbital structures.

Patients with dental-origin maxillary sinusitis typically experience a characteristic triad of symptoms: severe tooth pain, pressure sensation beneath the affected eye, and pain that worsens with head movement or bending forward. The orbital pressure results from inflammatory swelling that reduces the normal air space within the sinus, creating mechanical pressure on the thin bone separating the sinus from the orbital cavity.

Studies show that approximately 40% of maxillary sinusitis cases originate from dental infections, with upper molars being the most common source. The resulting orbital symptoms can include pain behind the eye, sensation of pressure or fullness, and occasionally mild diplopia due to mechanical effects on extraocular muscle function.

Chronic rhinosinusitis and persistent periorbital discomfort

Chronic rhinosinusitis creates ongoing inflammatory changes that can maintain persistent low-level orbital discomfort alongside dental symptoms. This condition often develops following inadequately treated acute episodes or in patients with underlying anatomical variations that promote sinus dysfunction. The chronic inflammatory state produces continuous pressure effects and neural sensitisation that manifests as persistent periorbital pain.

Chronic sinus inflammation creates a state of neural hyperexcitability that amplifies pain signals from multiple sources, explaining why patients often experience disproportionate discomfort from minor dental stimuli.

The persistent inflammation associated with chronic rhinosinusitis affects local blood flow patterns and neural function throughout the region. Patients frequently report orbital pain that fluctuates with weather changes, allergen exposure, or upper respiratory infections. This pain often correlates with periods of increased dental sensitivity, creating a cyclical pattern of discomfort.

Sphenoid sinusitis complications affecting Retro-Orbital regions

Sphenoid sinusitis represents a more complex condition that can create deep retro-orbital pain patterns. The sphenoid sinus sits deep within the skull base, adjacent to critical neural and vascular structures. When inflammation affects this sinus, either from spreading dental infection or primary sinusitis, the resulting pressure can create intense pain behind the eyes that patients often describe as boring or drilling in nature.

Dental infections that spread to involve the sphenoid sinus typically originate from severely infected maxillary molars with extensive periapical involvement. The infection spreads through fascial planes and bone marrow spaces to reach the sphenoid region. This creates a medical emergency requiring immediate intervention due to the proximity to critical intracranial structures.

Ethmoid sinusitis and medial canthal pain manifestations

Ethmoid sinusitis affects the complex network of air cells located between the nasal cavity and orbit. Inflammation in this region produces characteristic medial canthal pain that can be confused with dental pain originating from maxillary canines or premolars. The ethmoid air cells share thin bony walls with the orbit, making them particularly susceptible to creating orbital symptoms when inflamed.

Patients with ethmoid sinusitis often experience pain at the inner corner of the eye, nasal congestion, and sensitivity in the maxillary canine region. This combination of symptoms can create diagnostic challenges, as the pain patterns overlap significantly with dental pathology. Careful clinical examination and appropriate imaging studies prove essential for distinguishing between primary dental pathology and sinus-related referred pain.

Dental abscess complications and orbital cellulitis pathogenesis

Severe dental infections can progress beyond the confines of the alveolar bone to affect surrounding facial spaces and orbital structures. This progression represents a serious medical complication that requires immediate intervention to prevent vision-threatening outcomes. The anatomical pathways connecting the maxillary teeth to orbital structures provide direct routes for bacterial spread during periods of immune compromise or inadequate treatment.

Orbital cellulitis secondary to dental abscess typically originates from infected maxillary posterior teeth. The infection spreads through the maxillary bone marrow spaces or via lymphatic drainage patterns to reach the orbital soft tissues. Early signs include progressive swelling around the affected eye, pain with eye movement, and deteriorating vision. The bacterial organisms responsible typically include mixed anaerobic species similar to those found in severe periodontal infections.

The progression from dental abscess to orbital cellulitis follows predictable anatomical pathways. Infection initially spreads from the tooth apex into surrounding bone marrow spaces. If the immune response proves inadequate, bacteria can traverse the thin maxillary bone to enter fascial spaces communicating with the orbit. This progression occurs most readily in elderly patients, diabetics, or individuals with compromised immune systems.

Early recognition and aggressive treatment of dental infections with orbital involvement can prevent permanent vision loss and life-threatening intracranial complications.

Treatment requires coordination between dental and medical specialists to address both the source dental infection and the orbital involvement. Intravenous antibiotics, surgical drainage of the dental abscess, and sometimes orbital decompression may be necessary. The prognosis depends largely on how quickly appropriate treatment begins after the onset of orbital symptoms.

Prevention strategies focus on maintaining excellent oral hygiene, promptly treating dental caries, and seeking immediate professional care for signs of dental abscess. Patients with diabetes or other conditions affecting immune function should be particularly vigilant about dental health, as they face increased risks for severe complications.

Temporomandibular joint dysfunction and ocular symptom correlation

Temporomandibular joint dysfunction (TMD) creates complex patterns of referred pain that frequently extend beyond the jaw region to affect the temples, orbit, and periorbital areas. The TMJ maintains extensive neural connections with the trigeminal system, and dysfunction in this joint can trigger widespread pain referral patterns that confuse both patients and healthcare providers.

TMJ internal derangement and referred temple pain

Internal derangement of the TMJ involves displacement or dysfunction of the articular disc within the joint space. This mechanical problem creates inflammatory changes that affect surrounding neural structures, particularly branches of the auriculotemporal nerve. When these nerve branches become inflamed or compressed, they can produce pain patterns that extend into the temporal region and around the eye.

Patients with TMJ internal derangement often experience orbital pain that correlates with jaw function. The pain typically worsens with chewing, speaking, or jaw clenching, and may be accompanied by joint clicking or locking sensations. The referred pain occurs because the auriculotemporal nerve shares central processing pathways with ophthalmic division fibres of the trigeminal nerve.

Understanding the connection between TMJ dysfunction and orbital pain helps explain why some patients experience eye discomfort that seems unrelated to any identifiable ocular pathology. This knowledge proves crucial for developing appropriate treatment strategies that address the underlying joint dysfunction rather than focusing solely on symptom management.

Myofascial pain syndrome affecting pterygoid muscles

The pterygoid muscles play crucial roles in jaw function and maintain close anatomical relationships with neural structures affecting the orbital region. When these muscles develop trigger points or chronic tension, they can refer pain to distant locations including the temple, orbit, and behind the eye. This referral pattern occurs through shared neural pathways and fascial connections that link the masticatory muscles to periorbital structures.

Lateral pterygoid muscle dysfunction commonly produces pain that patients describe as deep behind the eye or in the temple region. The medial pterygoid muscle can refer pain to the ear, temple, and sometimes to the orbital area. These referral patterns occur because the pterygoid muscles receive innervation from branches of the mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve, which shares central processing areas with the ophthalmic division.

Treatment approaches for pterygoid muscle-related orbital pain focus on addressing muscle tension through physical therapy, trigger point therapy, and stress management techniques. Patients often experience significant improvement in orbital symptoms when underlying muscle dysfunction is properly addressed through comprehensive myofascial therapy approaches.

Bruxism-related muscle tension and periorbital strain

Chronic teeth grinding or clenching creates sustained tension throughout the masticatory muscle system, leading to pain referral patterns that can affect the orbital and periorbital regions. The masseter, temporalis, and pterygoid muscles all participate in bruxism activities, and when overused, they develop trigger points and referral patterns that extend beyond the immediate jaw region.

The temporalis muscle, in particular, can refer pain directly to the orbital and temporal regions when affected by chronic tension from bruxism. This large fan-shaped muscle extends from the temporal fossa to the coronoid process of the mandible, and when chronically contracted, it can produce persistent orbital discomfort that mimics other conditions.

Patients with bruxism-related orbital pain often report symptoms that are worse in the morning, correlating with periods of increased grinding activity during sleep. The pain may be accompanied by jaw stiffness, headaches, and sensitivity in the temporal region. Treatment typically involves fabrication of occlusal guards to protect the teeth and reduce muscle tension, combined with stress management and muscle relaxation techniques.

Cluster headache variants with dental pain presentation

Cluster headaches represent a distinct neurological condition that can create pain patterns involving both the orbital region and dental structures. These severe headaches occur in cyclical patterns and typically affect one side of the head, creating intense pain around the eye that can radiate to the maxillary teeth. The neurological mechanisms underlying cluster headaches involve dysfunction of the hypothalamus and trigeminal-vascular system, creating pain patterns that can be confused with dental pathology.

The characteristic presentation of cluster headache includes severe, stabbing pain centred around one eye, accompanied by autonomic symptoms such as tearing, nasal congestion, and eyelid drooping. However, some patients also experience significant discomfort in the maxillary teeth on the affected side, leading to confusion about the primary source of their pain. This dental component occurs because the trigeminal nerve pathways involved in cluster headache also innervate the maxillary dentition.

Differentiating cluster headache from dental pathology requires careful attention to the temporal patterns of pain, associated autonomic symptoms, and response to specific treatments. Cluster headaches follow predictable circadian patterns, often occurring at the same time each day during active periods. The pain is typically described as boring or stabbing, rather than the throbbing or aching quality associated with dental infections.

The cyclical nature of cluster headaches and their association with autonomic symptoms help distinguish them from primary dental pathology, even when significant tooth pain accompanies the orbital symptoms.

Treatment for cluster headaches differs significantly from dental pain management approaches. High-flow oxygen therapy, triptans, and preventive medications such as verapamil form the cornerstone of cluster headache treatment. Patients who receive inappropriate dental treatment for cluster headache-related tooth pain typically experience no improvement and may undergo unnecessary procedures.

Healthcare providers must maintain awareness of cluster headache variants that present with prominent dental symptoms. The key distinguishing features include the severe, stabbing quality of the orbital pain, presence of autonomic symptoms, cyclical timing patterns, and lack of identifiable dental pathology on clinical and radiographic examination.

Emergency red flag symptoms requiring immediate medical intervention

Certain combinations of tooth and eye pain indicate serious conditions requiring urgent medical attention. These red flag symptoms suggest potential complications such as spreading infection, orbital cellulitis, cavernous sinus thrombosis, or other life-threatening conditions. Healthcare

providers should be aware of these warning signs and ensure patients understand when to seek emergency care rather than waiting for routine appointments.

Progressive swelling around the eye combined with tooth pain represents one of the most concerning presentations. This combination suggests possible orbital cellulitis or preseptal cellulitis secondary to dental infection. The swelling typically begins as mild puffiness but can progress rapidly to complete eye closure within hours. Patients may also experience fever, malaise, and worsening pain that does not respond to standard pain medications.

Vision changes accompanying dental pain require immediate evaluation by both dental and medical professionals. These changes can include blurred vision, double vision, loss of visual field, or complete vision loss. Such symptoms suggest possible compression of the optic nerve or involvement of extraocular muscles due to spreading infection or inflammatory processes. Any vision change in the context of dental infection should be treated as a medical emergency until proven otherwise.

High fever exceeding 101.5°F (38.6°C) combined with tooth and eye pain indicates systemic involvement that requires urgent intervention. This presentation suggests bacteremia or spreading infection that could potentially involve intracranial structures. Patients may also experience confusion, neck stiffness, or altered mental status, which are particularly ominous signs requiring immediate hospital evaluation.

Severe headache with sudden onset, particularly when accompanied by nausea, vomiting, and photophobia alongside dental pain, may indicate increased intracranial pressure or meningeal involvement. This constellation of symptoms requires emergency department evaluation to rule out conditions such as cavernous sinus thrombosis, brain abscess, or bacterial meningitis secondary to dental infection.

The proximity of maxillary teeth to critical anatomical structures means that seemingly routine dental infections can rapidly progress to life-threatening complications without appropriate intervention.

Difficulty swallowing or breathing combined with facial swelling and dental pain suggests involvement of deeper fascial spaces that could compromise the airway. Ludwig’s angina, though more commonly associated with mandibular infections, can occasionally result from maxillary infections that spread to involve multiple fascial planes. This condition requires immediate airway management and aggressive antibiotic therapy.

Patients experiencing any combination of these red flag symptoms should be instructed to seek immediate emergency care rather than attempting home remedies or waiting for dental appointments. Healthcare providers must maintain a high index of suspicion for serious complications when evaluating patients with concurrent dental and ocular symptoms. Early recognition and appropriate referral can prevent devastating complications including permanent vision loss, brain abscess formation, and septic shock.

Emergency departments should be equipped to manage these complex presentations through coordination with both dental and ophthalmological consultants. Initial management typically includes intravenous antibiotics, pain control, and immediate imaging studies to assess the extent of infection spread. The specific antibiotic regimen should provide coverage for typical oral flora including anaerobic organisms commonly involved in severe dental infections.